What should a middleman mediate?

Monday, November 5, 2007

In yesterday’s New York Times Magazine, Rob Walker wrote a piece about “Buddylube,” a middleman agency that specializes in making widgets for pop bands:

“The artists need promotion,” Eaton summarizes. “And all these new technologies of social media need artists.” So what if there was “a one-stop shop” — a Jiffy Lube, if you will — for celebrity-centric social media? Since then Buddylube has established itself as a middleman — Eaton prefers “concierge” — between dozens of social-media companies and scores of music stars (well, the Web presences of scores of music stars). Eaton compares the use of these tools with the kind of community-specific promotion that bands have always used — except that instead of putting up fliers in a particular geographic location, the target is virtual: Like offering a “skin” that decorates your Snapvine voice-mail player with a picture of Enrique Iglesias.

There is a bit of an implication, which Walker conveniently uses me to counter, that there is something insincere or artificial about a “concierge” mediating the relationship between rock star and fan, not unlike the Facebook fakesters I wrote about here. The point I’m quoted as making is that giving fans a way to spread your music around to other fans and potential fans is inherently positive. It says to the fan “I realize that you are an important part of my success, and here are some free tools that will give you pleasure and help you fill that role.”

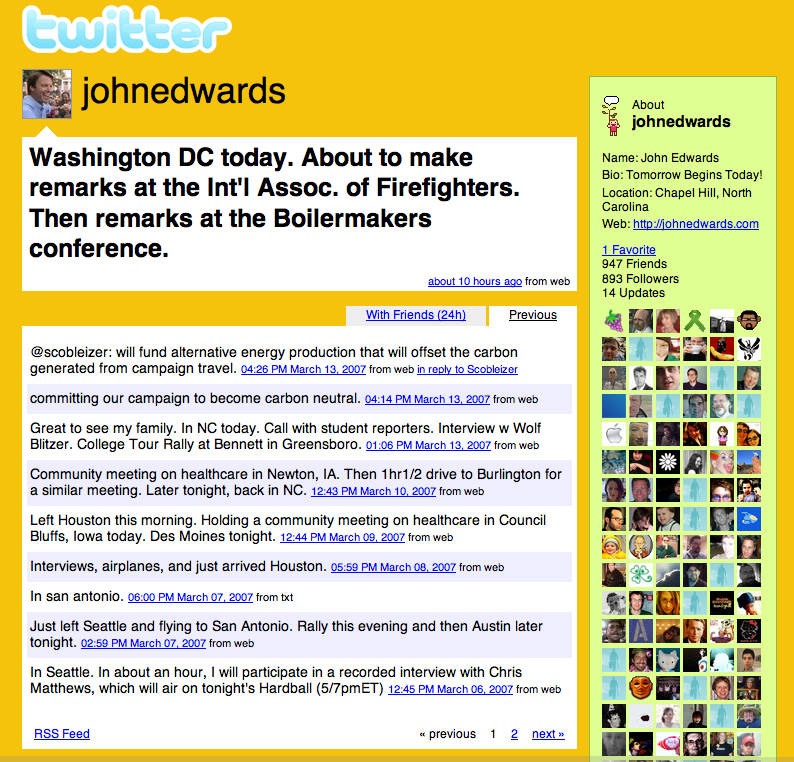

I don’t think audiences expect that everything that comes from a band, or celebrity or — and Walker makes this link at the very end — politician will come directly from the hand of the one it represents. We’re used to publicists, spokespeople and speech writers. And we can do math and figure out that if someone has 10 fans, we’ll probably get things straight from the human in question but that this won’t scale to thousands, and certainly not to hundreds of thousands or millions. There is a real market for middle-people, and so long as there is no deception going on about it, I think that is just fine. It would be far worse to omit the middle people and skip the communication altogether.

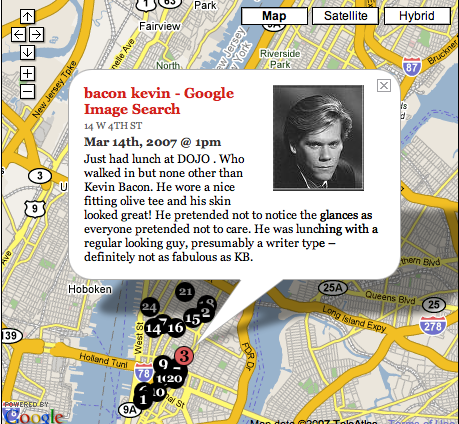

What strikes me, though, is the extent to which this relationship-moderator market seems focused on filling out forms — fill in the blanks to create a widget, insert your video here to include moving images, add photos here, link to mailing list goes here, etc. Create a street team by signing up here and clicking this link to do this or that.

Once everyone’s got the technology down, they will realize that communication is not just about form, but about how the form is conveyed. It is about style as well as substance, or, as we hammer over the head in our communication courses, it’s about the relational messages that are sent as well as the content messages. Technomiddlemen are getting very good at crafting content messages and so long as not everyone has them, that’s enough. The mere existence of the thing is enough to send the message. But when everyone’s got them, the relational subtleties will matter even more than they already do. Understanding the tone to strike for each artist given his or her fanbase (and desired fanbase) is a sophisticated communication task — how do you speak to the new fan and the die hard at the same time? the casual listener and the devotee? PR professionals, artist managers, and their ilk are generally trained — through practice if not schooling — to speak to crowds. Speaking to crowds while also speaking to individuals and making it feel interpersonally meaningful is an increasingly important task that no technology can solve.